Jul 2, 2020Potato industry still feeling effects of foodservice shutdowns

Now three months into the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, the situation remains fluid and unsettled for the potato industry and that likely will continue for quite some time.

When massive foodservice restrictions and shutdowns went into place the second week of March, it threw the food supply chain into a tailspin. Schools closed, tourism halted and restaurants were limited to drive-thru and take-out only.

In 2019, an all-time high of 58% of U.S.-grown potatoes went to the foodservice, led by frozen fries. McCain Foods, the world’s largest producer of frozen potato products, has production facilities in the U.S. and Canada. Christine Wentworth, McCain’s vice president of agriculture procurement, said the effects were felt immediately, as restaurants and other foodservice customers began canceling orders.

The National Restaurant Association reported that foodservice sales in the U.S. were off $120 billion during the months of March, April and May, which is more than a 40% drop of what they were last year. Lack of foodservice demand worldwide also led to U.S. export numbers for frozen potato products to drop 29% during April, year-over-year, reported Potatoes USA.

The lack of demand for fry makers put them in a position to make “painful” decisions, Wentworth said. That included shutting down lines or temporary closing plants — although in some cases, due to an employee testing positive for COVID — as well as furloughing employees. Businesses, including farms and processors, have had to invest in protective measures to help stem the spread of COVID and protect their staffs and customers, which Wentworth said is the top priority.

Those are just internal ramifications for the fry makers. Externally, processors began telling their grower partners earlier this spring not to count on them buying as many processing potatoes in 2020. Without a guaranteed buyer, many growers who plant processing potatoes reduced acreage. The result is a projected 6% drop in acreage for U.S. growers this year. Fewer acres and uneven processing demand, which has improved in June as restaurants began to reopen in limited capacity, has left uncertainty surrounding the 2020 harvest and if it will be large enough to sustain demand until the 2021 crop is ready, since no one really can predict what foodservice demand is going to look like for the next six months to a year.

The COVID situation and initial surplus in processing potatoes had many growers giving away spuds to food banks and the general public not only to assist those who might be in need, but also to get them out of storage bins to make way for the 2020 crop.

On the flip side, retail sales of potato products saw a big jump once COVID hit and people were staying home. Sales have remained elevated by double-digit percentages and as high as 30% in some frozen and shelf-stable produce product categories. Between March 16 and May 17, fresh potato sales in retail were up 44% by volume, while frozen and dehy were up more than 50%, reported Potatoes USA.

“If there is a good thing out of this, it’s that people turned to potatoes right away,” said Blair Richardson, CEO, Potatoes USA. “A lot of people cooked their first potatoes at home during the past 90 days.”

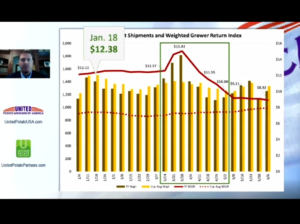

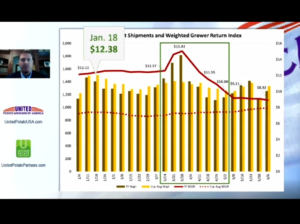

Weighted grower return index (GRI) averages for russet shipments — which includes potatoes for fry processing — were stable in the $12 to $12.50 range from Jan. 1 through early March. They initially spiked to $15.03 by the week of March 28, but have since declined and were under $9 by early June, as the early retail boom leveled off and unused, free potatoes in storage began reaching the public consumers.

The fresh and chip markets — which, along with frozen, represent the three largest segments of the potato industry — are more prominent in retail than foodservice. Predictably so, growers who depend greatly on fresh and chip demand haven’t been as negatively affected as farms who sell mostly to fry makers. Acreage in Michigan, which produces more chip potatoes than any state, is expected to be stable this year. In Colorado, where farms widely grow for the fresh market, acreage is expected to be up about 4%.

Black Gold Farms has growing operations in 10 states, including the Red River Valley, Great Lakes region, Texas and other southern states. Black Gold CEO Eric Halverson and COO John Halverson gave a virtual presentation during the United Fresh show in June. Things have been stable at Black Gold, but the Halverson brothers acknowledged they were positioned well because their operation sells heavily to the fresh and chip markets.

“The retail market has been really strong,” John Halverson said June 18. “In the last two to three weeks, we have felt demand going back to foodservice, but the retail demand hasn’t softened up as much as the foodservice has come back.”

USDA help

In April, as the food supply chain clogged amid the lack of foodservice demand, the U.S. Department of Agriculture announced the $19 billion Coronavirus Food Assistance Program (CFAP), which designated $2.1 billion for the specialty crop industry, with the rest going to commodity, livestock and dairy producers.

Despite $50 million in Section 32 purchases of fresh potatoes, which is actually a record purchase, the way CFAP funds are delegated has greatly underserved specialty crops, NPC CEO Kam Quarles has repeated in recent weeks.

“Less than 2% of (CFAP distributions) so far have gone to fruits and vegetables,” said Quarles, who added that the scope of the potato industry and its reliance on foodservice was not properly taken into account when the USDA designed the program. He said the losses the industry has experienced well exceed USDA thresholds for larger payment distributions, known as Category 1.

Quarles said the errors in the CFAP format are understandable since it was a massive and unprecedented undertaking for the USDA, but he and other specialty crop leaders are pleading with the administration to alter its delegation system and to come through with more “meaningful” relief. The USDA has been receptive to the pleas, Quarles said. The NPC also is pushing for more purchase of already processed potato products and inclusion of larger packs of potatoes to address raw processing surplus.

National Potato Council CEO Kam Quarles leads a press conference in front of the Capitol on Feb. 26, 2020. Photo: Bill Schaefer Photography

“I am going to continue to be an optimist,” Quarles said of more USDA help. He added that more agriculture funds could come with the next federal coronavirus stimulus package. Industry leaders are hopeful the Senate will draft a bipartisan stimulus bill with agricultural provisions that has a good chance of being signed by President Trump, unlike the $3 trillion, largely partisan HEROES Act that the House passed in May.

“(Rep.) Collin Peterson (D-Minnesota) did a lot of hard work on the House bill,” Quarles said. “I don’t think we should sell short the amount of effort he put in. Hopefully, the Senate is going to improve upon those (agriculture) provisions.” Added Randy Russell of lobbyist firm Russell Group DC: “The ag provisions were largely bipartisan, so that’s good.”

As far as a timeline on a Senate bill, NPC leaders are hopeful for something in late July or early August. “It’s an election year and we’re all watching the calendar,” said NPC President Britt Raybould. “If they’re (the Senate) going to do something, it’s likely going to be before the August recess (which begins Aug. 7).”

Crop protection update

Thus far, COVID-19 has not caused a disruption, said ADAMA US CEO Jake Brodsgaard, although he’s watching the situation very closely.

“We don’t anticipate any crop protection product shortages at this time, but it will depend on the rate of COVID infection and how it’s handled by manufacturing plants,” Brodsgaard said. “I think at this time it is not a matter of if, it is a matter of when. This could mimic recent patterns in the meat processing industry. All ADAMA plants are taking great measures to mitigate risk of shutdown if and when workers may become exposed to COVID.”

Brodsgaard said that China loosening up environmental restrictions to open up more factories may lead to a raw materials price decline, but doubts that will be long-term. He stressed that it’s “business as usual” manufacturing and shipping of crop protection agents, but that can change at any time should COVID start affecting plant employees.

As far as the Environmental Protection Agency’s regulation and approval rate of crop protection agents, Brodsgaard has seen little change.

“Our relationship with EPA has been business as usual for the most part, with some slow down due to work-from-home setbacks,” he said.

RELATED: How COVID-19 is backing up the potato supply chain