Aug 22, 2018Take steps to get to the root of weed control failures

Controlling weeds is one of the most challenging parts of vegetable production. It is especially frustrating when the time and money you invest do not yield the weed control you had hoped for.

Herbicide resistance is one of the first culprits we think of when control failures happen. However, control failures can happen for many reasons, including too little or too much rainfall, equipment or operator error, or weed emergence after pre-emergence products have dissipated. How can you know if resistance is the issue, or if something else is at the root of control failures?

When scouting the field ask yourself a few questions. Are there multiple species that have escaped control? Is there a pattern to the distribution of the escaped weeds? Were the weeds greater than 4 inches in height or flowering at the time of application? If the answer is yes to any of these questions, there may be another explanation for failed control.

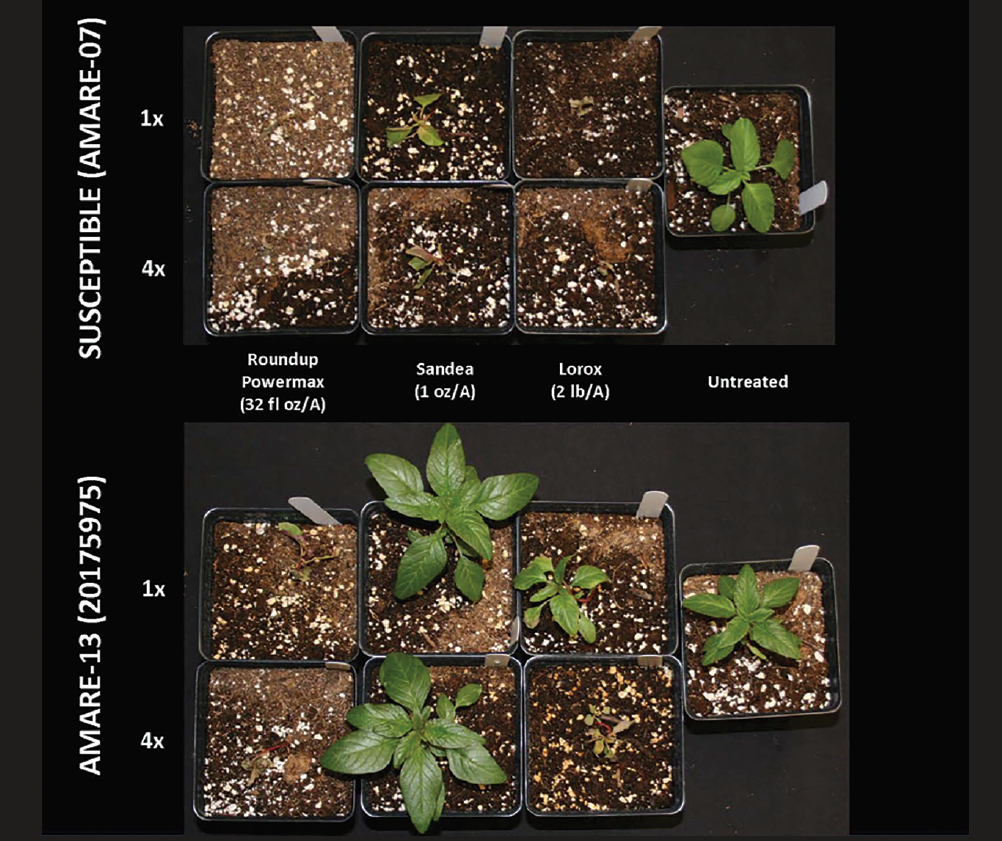

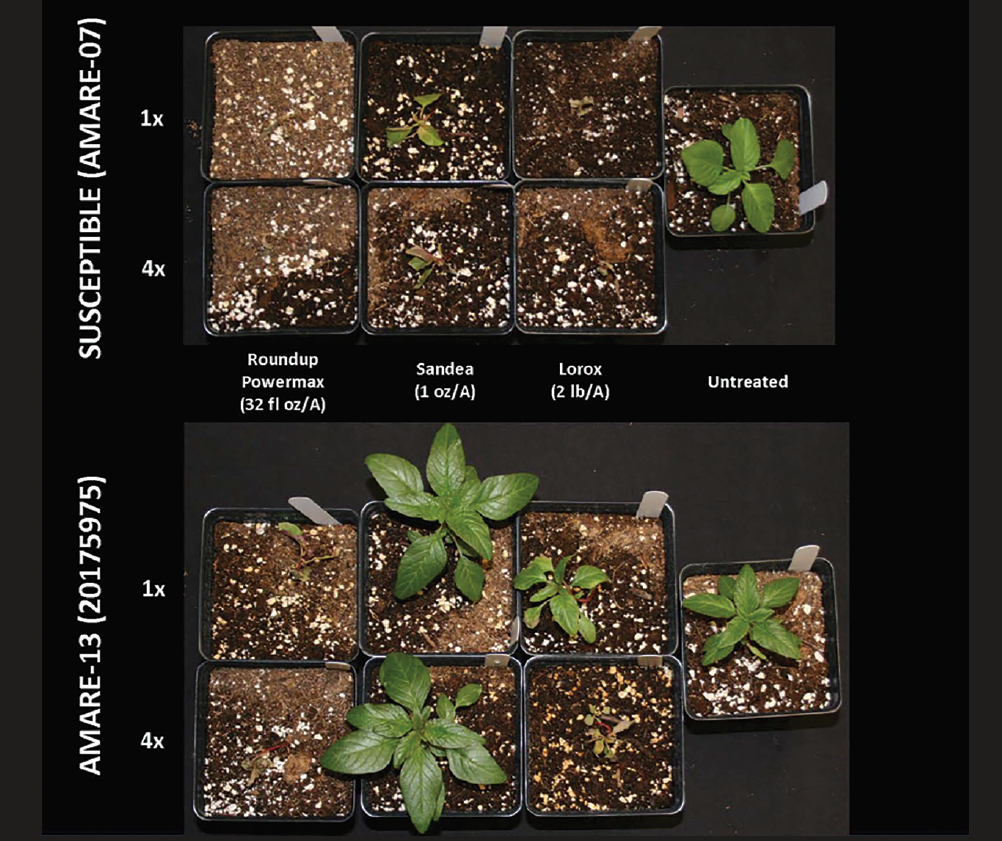

If the answers are no, Michigan State University (MSU) Diagnostic Services can screen for herbicide resistance to common weeds, including Powell amaranth, redroot pigweed, waterhemp, common lambsquarters, giant and common ragweed, and marestail. For example, in summer 2017, we collaborated with MSU Horticulture Professor Bernard Zandstra to screen pigweed from asparagus fields for herbicide resistance. Pigweeds have been a challenge for asparagus growers. Grower experience suggested some of the herbicides they had relied on for control were not working as well as they have in the past. Was this due to resistance, or something else? The lab provided evidence that there is resistance to linuron (Group 7 photosynthesis inhibitor) and halosulfuron (Group 2 ALS inhibitor) in many of the problem pigweed populations we sampled. However, there was no evidence of resistance to 2,4-D, glyphosate, or sulfentrazone. This information can help growers decide which products to invest in for pigweed control.

How can you go about testing your weeds for resistance? There are a few key considerations to ensure that the lab can test your sample.

Collect seedheads from plants that have survived one or more herbicide applications from multiple places throughout the field. A minimum of five plants is suggested with more being beneficial. Make sure you are harvesting ripe seed. For example, for redroot pigweed or Powell amaranth, seed should be black when you rub the seedhead in your hands. Also, make sure you harvest the parts of plants that have seed. For example, the female flowers in common ragweed are located in the leaf axils, not at the tip of the plant (even though the male flowers at the tips look like seedheads). Last, package the seedheads you collect in a paper bag inside a box or large envelope. Plastic bags create condensation and vegetation can rot. Mail the seeds to MSU Diagnostic Services, 578 Wilson Rd., Room 107, East Lansing, MI 48824.

A submittal form and resources with photos to help you are located at www. pestid.msu.edu/herbicide-resistance.

– By Ben Werling and Erin Hill, Michigan State University Extension

Above: An example of results of a screen for herbicide resistance for redroot pigweed from an asparagus field. Seed from a susceptible check population was killed by Lorox and Sandea, but seed from the grower’s field survived at the labeled (1X) rates, indicating resistance. Photo: Michigan State University