Dec 7, 2020Georgia explores options for reducing soilborne pathogens

Georgia growers can grow watermelons without methyl bromide fumigation – they just need several other tools to pick up the slack.

That’s the message University of Georgia Assistant Professor Abolfazl Hajihassani had in a paper his lab wrote for the Georgia Watermelon Association.

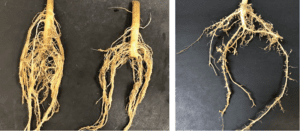

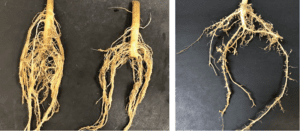

Methyl bromide fumigation was used to clean out soil pathogens before it was phased out in 2005 due to environmental concerns for the ozone layer, groundwater and beneficial soil microorganisms. Without it, major concerns for growers are root-knot nematodes and fusarium wilt, and Hajihassani – a specialist in nematodes – was hired in 2017 by the university to work on the issue.

Other soil fumigants are available, he said. Growers also can use watermelon plants grafted onto rootstocks with natural disease resistance, and use non-chemical control practices such as crop rotation and planting cover crops that reduce the presence of nematodes in soil.

“By using only cultural practices, however, it is hard to achieve enough control for proper production of watermelon,” Hajihassani said.

Other chemistries

Hajihassani said some of the other fumigants available for root-knot nematodes are Telone II (a.i. 1,3-D dichloropropene), Vapam (metam sodium) and chloropicrin.

“Methyl bromide was a very good chemical pesticide to control different pathogens,” he said. Other currently available fumigants have “some efficacy” but are not replacements. Non-fumigant nematicides that are registered for use in watermelon are Nimitz (a.i. fluensulfone), Vydate (oxamyl), Velum Prime (fluopyram) and Movento (spirotetramat).

Cultural practices

Several cultural control practices may also help reduce pathogens.

Although labor-intensive, removing residual plant roots from the soil has been shown to reduce nematode populations by 90%. Soil can also be “solarized” or heated by covering it with clear plastic to trap sun rays and kill off nematodes with temperatures above 100˚ F, but Hajihassani points out this also kills off beneficial microbes.

Some cover crops are known to be effective for root-knot control. Hajihassani’s lab found that Mucuna pruriens (velvet bean), Aeschynomene americana (joint vetch), Tagetes spp. (marigold), Crotalaria juncea (sunn hemp) and some cultivars of sorghum-sudangrass (Sorghum bicolor × S. arundinaceum) have been successfully used in the South as cover crops for root-knot control.

Grafting rootstocks

While breeders have looked for natural resistance to root-knot nematodes, finding a watermelon variety strong enough to bring to the commercial market has been difficult.

“As far as I know, there are no commercial resistant varieties on the market,” Hajihassani said. “Most of the resistance that has been found in the past has been in multiple lines or accessions of watermelon that cannot be used as commercial varieties because of lacking horticultural and/or agronomy traits such as flavor, color and crop productivity (yield). And transferring that resistance from those watermelon lines to commercial varieties is not possible – at least, at the time we’re talking it hasn’t successfully been done.”

While their fruit may be unmarketable, disease-resistant cucurbits are still of use as rootstock into which melon vines may be grafted. For instance, Hajihassani said, the hybrid squash and bottle gourd rootstocks have shown resistance to fusarium wilt, but not root-knot nematode. In contrast, citron melon, called Carolina Strongback, has resistance to both pathogens.

“These grafted plants are still not common; the growers are not usually using them, because of their high price,” he said. “In fact, these are costly compared to using the pesticides (nematicides and fungicides) and non-grafted watermelons. To me, the use a rootstock that has resistance to both pathogens seems ideal. … If you’re suppressing two pathogens with only growing one resistant rootstock, that would be beneficial, not only in terms of the economic value but in terms of reducing the environmental concerns associated with the use of chemicals.”

While some researchers have looked at robotic systems for reducing the cost of grafting, for now, grafting remains costly in terms of labor.

“The growers need something that can not only be justified economically, but also helpful for them,” Hajihassani said. “Finding a solution like improving grafting technology to effectively control these pathogens will be a ‘must win’ for growers.” In the meantime, Georgia growers can still beat fusarium wilt and root-knot nematodes with current options, but there are no cheap-and-easy shortcuts to doing that.

— Stephen Kloosterman, associate editor