Jul 22, 2020Swede midge, a threat to Brassica crops, now in Pennsylvania

Another invasive species, the swede midge, has made its way to Pennsylvania. Swede midge is a tiny, 1/16 inch long fly that can be a serious pest of Brassica crops, also known as cole crops, and weeds.

Native to Europe and parts of Asia, this pest was confirmed in New York about 20 years ago and has spread to additional states and Canada. This midge belongs to a group of insects that are known to be host-plant specialists, often causing galls or other induced plant growth patterns. The swede midge fits this pattern, being tightly connected to a plant family, and larval feeding induces changes in plant physiology, resulting in various forms of distorted growth.

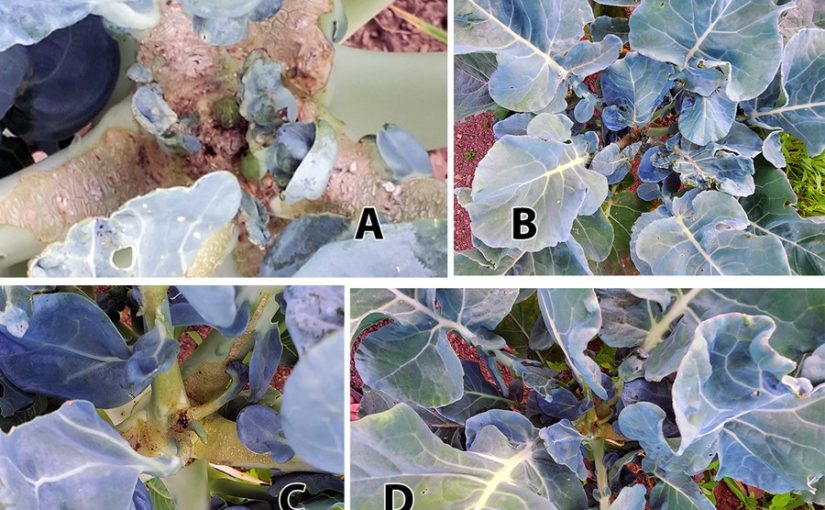

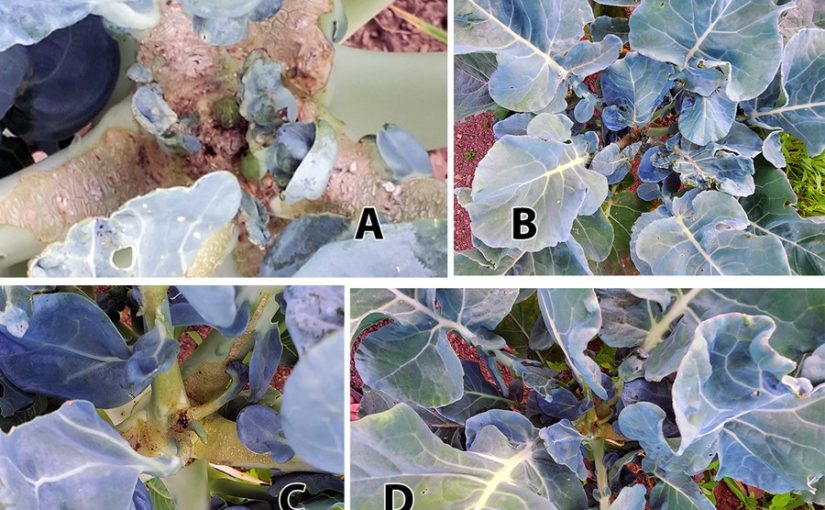

We discovered swede midge by responding to a grower’s problem in broccoli on July 16, 2020, in Bradford County. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first occurrence of swede midge in Pennsylvania. However, the damage has been mistaken for molybdenum injury, herbicide injury, and various abiotic stress factors. Swede midge may be more widespread in Pennsylvania, but damage misdiagnosed, or it may exist in weeds or crops that are planted at higher densities, such as Brassica cover crops.

Entomologists working in infested areas have done a great job pulling together a Swede Midge Information Center and all the information in this article comes from those sources.

Damage varies with the crop and time of infestation. Symptoms include scarring at the growing point resulting in a ‘blind head’, leaf puckering, multiple shoots and growing points, many small heads, brown corky scarring, swollen flower buds/florets or leaves, and other plant growth distortions. Secondary soft rot infections can also occur. There is no host-plant resistance, but there is variation in susceptibility among plants. The problem at the farm in Pennsylvania was with broccoli, cauliflower, and brussels sprouts not producing any heads.

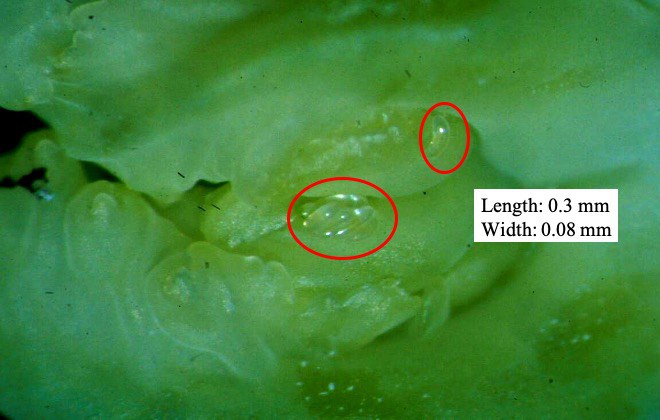

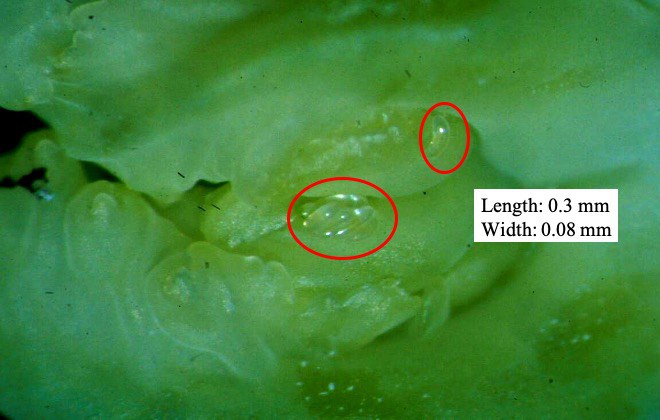

Swede midge females lay their eggs deep in the heart of cruciferous plants. They like the youngest actively growing tissue. Eggs are initially transparent becoming creamy yellow as they near maturity, and microscopic and cannot be seen with the naked eye. Image: Cornell University

Swede midge overwinter as pupae and emerge in several flushes in the spring. Adults are very short-lived (less than a week), and poor fliers. Adults mate and lay eggs in the developing leaves that make up the growing tip, and larvae feed at within these growing tips, which protects them from contact insecticides. Larvae feed for 1 to 3 weeks, then jump to the ground, and pupate in the upper half-inch of soil. There are multiple generations per year.

Eggs hatch into larvae, which are 3-4 mm in size at maturity. They are clear when they first hatch and become more creamy white or yellow. As they near maturity, they have the capability to curl up and flip or jump off of the plant to the ground. Swede midge larvae feed gregariously (in groups), during feeding, larvae produce a secretion that breaks down plant tissue, creating a moist environment. The secretion is toxic to the plant and results in swollen tissue, abnormal growth, and brown scarring that ultimately can result in reduced yield and unmarketable produce. Image: Cornell University

Management is tied to their ecology. Strategies that remove a host resource can be effective. This includes rotation, sanitation (e.g., clean harvest), and avoiding Brassica cover crops. Recent research on how to ‘crash’ swede midge populations on a farm through careful timing of crop rotation in space and time, along with updated information on relative preference among 14 different Brassica hosts, is summarized in a free pdf download, New Crop Rotation Recommendations for Swede Midge.

Systemic insecticides are effective. Organic insecticides have given only partial control. Multiple kaolin clay applications may be among the most effective organic spray options. Careful application of insect netting is an expensive but effective option. There has been a tendency for this pest to be more of a problem on smaller, diversified farms, and organic farms.

Peel back leaves of the suspect growing tip and look for larvae. Swede midge larvae break down plant tissue creating a very moist environment – you will see the moisture in an infected tip compared to a healthy one. Image: Cornell University

If swede midge is indeed rare in Pennsylvania, the best management tactic now may be early detection, which would allow management to be directed at very low and scattered populations. Sex pheromone lures that only attract males are available, and trapping protocols developed in northeastern states and Canada. The midges are small (think the size of spotted wing drosophila larvae – you will want a hand lens when searching for them) and can be hard to identify. Efforts to establish early detection would take some skill and organization.

– Shelby Fleischer, Francesco Di Gioia and John Esslingen, Penn State University

Photo at top: Brown corky scarring is not limited to the growing points and leaf petioles, but can also cause damage in the heads of cauliflower. Image: Cornell University