Nov 21, 2022Locati Farms counters higher costs, supply shortages

Locati Farms, a Walla Walla, Washington, sweet onion grower, adapts to challenges by changing growing practices and using technology to improve the quality of the region’s namesake onion. For more than a century, Locati Farms – now in its fourth generation – has grown sweet onions in the foothills of eastern Washington’s Blue Mountains.

Like other growers, Locati Farms has adjusted the way it does business to continue to remain profitable. Soaring input costs are among the farming operation’s most pressing issues, which also include labor and weather factors. Every year, Locati struggles to secure qualified crews to harvest, pack and ship the onions, said Mike Locati, owner operator.

To counter supply shortages and receive parts and products like fertilizer and tires when needed, Locati plans five months out. In case a second unit won’t be available when needed, Locati pre-purchases, doubling orders on replacement parts. The downside, of course, is higher up-front costs and difficulty making purchasing decisions in the winter before a crop takes shape.

Locati grows on 500 acres. The open-pollinated sweet onions are planted in September with harvesting commencing in mid-June through mid-August.

In the 1990s, Locati Farms began using drip irrigation. Initially, that decision was based on labor costs, not water conservation: drip irrigation was less expensive than manually moving a 40-foot hand line pipe. Water conservation, however, is the bigger factor now.

“Drip and pivot are important for conserving water,” Locati said.

Land stewardship

Crop rotation and cover crops also help water efficiencies. Locati said he has seen overused ground, mined of its production capabilities.

“We try where we can to raise cover crops,” he said. “We don’t try to leave the ground fallow. The ground is alive as much as we are. We have to treat it that way.”

Locati Farms rents acreage to help move crops around, employing four- or five-year rotations. Wheat, peas, field corn and alfalfa are the principal rotation crops.

In the late 2010s, Locati Farms began using Sudan grass and occasionally wheat as cover crops. The practices have helped Locati Farms better find water.

“As that becomes more and more available, cover crops become easier to do,” Locati said.

Typical pests and diseases include onion thrips and fungal disease. Onion white rot, which can be in the ground for more than 20 years before discovery, infects bulbs with white rot spores, wilting leaves while rotting the onion’s bottoms, preventing reproduction and producing an unmarketable crop.

Cooperation with university Extension personnel is important. Locati Farms has long been an Extension cooperator, hosting many production and white rot trials.

“We couldn’t do what we do without them,” Locati said. “It lets us gain knowledge in different ways to do things and solve problems.”

Technology factor

Technology plays a prominent role in Locati Farms’ success. While some processes, namely harvesting, require manual work, GPS on tractors and other technology helps efficiently manage irrigation and other elements. In the packinghouse, machinery has replaced hand sorting while computers manage the packing line through auto stacking.

Unlike storage onions which are mechanically harvested, Walla Walla sweets are more delicate, and are hand-picked to avoid damage. The onions are cut while green and dried in the fields. “Hand harvesting is the biggest area of improvement,” Locati said. “It’s the hardest to find a technology to replace. That’s the area (where) we could really use it.”

Hand-selected, Locati’s heirloom seed originated from the original sweet onion seeds brought to Walla Walla in 1905 from Corsica, Italy, by Pete Pieri, a French immigrant who employed Joe Locati, Mike’s great-grandfather.

In 1909, Joe Locati started his own farm raising sweet onions on five acres. In the 1940s, his sons, Ambrose and Pete, took over. In 1949, cousin Virgil Criscola joined the brothers in constructing the Walla Walla Valley’s first onion-packing shed.

Michael F. Locati, one of Ambrose’s sons, ran the business until 2015 when his nephew, Michael “Mike” J. Locati, son of Ambrose “Bud” Locati Jr., took ownership. In the process of retiring, Michael F. Locati is less involved in daily operations, but focuses on overall planning, including future opportunities.

Mike Locati credits his uncle for co-founding the Walla Walla sweet onion federal marketing order.

Mike Locati grew up in the family business, working summers and weekends. After graduating from Washington State University with an agriculture technology and production management degree, he worked in the crop protection industry for six years.

Mike Locati increased his farm involvement after his father Ambrose Locati Jr., requested he take on more of his farming responsibilities.

“I am grateful for the life skills I learned, because not everyone learns those,” Mike Locati said. “At 115 years for a farm that started on five acres, that’s something to be proud of. Some days, we may complain, but there’s a lot of satisfaction in overcoming obstacles, and seeing the light at the end of tunnel, even if it gets kind of rocky.

“As stressful as it is, it’s a joy to be able to work for yourself.”

— Doug Ohlemeier, assistant editor

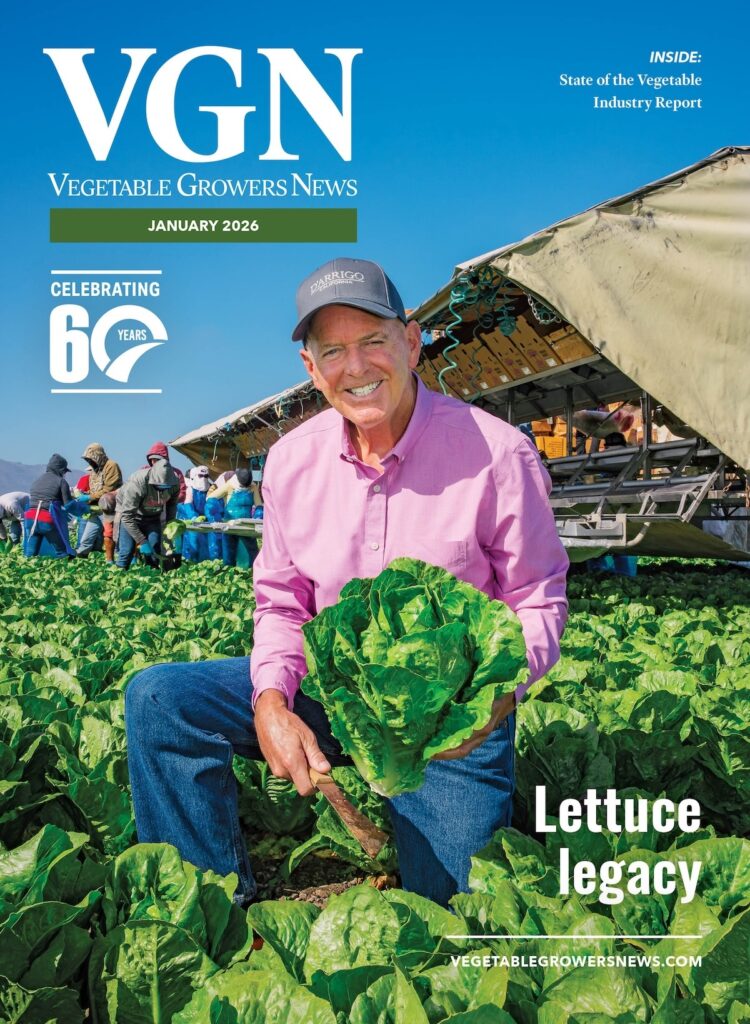

Photo: Mike Locati of Locati Farms views Walla Walla sweet onions. For more than a century, Locati Farms has grown sweet onions in the fertile Walla Walla Valley in the foothills of eastern Washington’s Blue Mountains. Photo: Doug Ohlemeier