Aug 21, 2023Weather disrupts California processing tomato harvest

As California growers harvest this season’s processing tomato crop, there is concern that canneries could struggle to keep up with a backlog of fruit deliveries.

Yolo County farmer Bruce Rominger, board chairman for the California Tomato Growers Association, said growers are worried about risks to fruit that can’t be processed right away.

“A cannery might say, ‘I’m going to contract with growers to bring me 200 loads per day,’” Rominger said. “Well, now all of a sudden, there’s 400 loads that need to be harvested. So the concern is we’re all jammed up, and some tomatoes sit in the field too long and get rotten.”

‘Raining like crazy’

After three years of drought, heavy rains left tomato fields wet and muddy through spring, disrupting planting of processing tomato transplants, which continued through May.

“It was raining like crazy in March, so nobody could really get in and plant. We didn’t plant until about April 12, so we were basically three weeks to a month late,” said Rominger, who also grows rice, nut crops, sunflowers, wheat, corn and seed crops. “We have more tomatoes scheduled to be harvested in October this year than we ever have before because of the late spring.”

To adjust for a bottleneck of trucks arriving at canners, which run 24-hour days during harvest, Rominger said some growers may be encouraged to harvest early when tomatoes are a little green. Under contracts with processors, Rominger explained, growers usually agree to deliver a certain tonnage during specific weeks to keep a consistent flow of tomatoes moving into canneries.

Colusa County farmer Mitchell Yerxa, who also farms processing tomatoes in Sutter County, said he usually begins harvest in early July. This year, it began a month later.

“This looks like one of those years where we might actually hit our full tonnage before we even get to the end of the season,” Yerxa said. “So it will be interesting to see if the canneries decide to take the tomatoes or not.”

In years of low yields, Yerxa said canners would accept an additional 10,000 or 40,000 pounds. This season, he said, they are telling growers they do not plan to accept more tonnage than was contracted.

Yerxa said many growers in the Sacramento Valley expect harvest to continue into October, a risky time due to the potential for wet weather. He said he and other growers insured the crop against rain damage “to make sure that we are protected.”

“With all the September loads being pushed to October,” he added, “the problem we really foresee is if we have a fall rain — a big one — and we can’t get the crop out.”

Record price agreement

The state’s tomato processors contracted 12.7 million tons of processing tomatoes this year, and acreage is estimated to be 254,000, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture processing tomato report released May 31. Fresno County remains the state’s top processing tomato region with an estimated 62,300 acres, followed by Merced, San Joaquin and Kings counties.

Despite the planting delay, wet weather has meant improved water allocations for San Joaquin Valley farmers. Growers who rely on water from the federal Central Valley Project and State Water Project received 100% of their surface water allocations—a relief after three straight drought years with limited or zero water supplies.

Mike Montna, president and chief executive officer of the California Tomato Growers Association, said more tomatoes were planted as a result, though the late timing of the water allocations meant this did not apply universally to growers.

“Last year, after the price was settled, we saw fuel and fertilizer really shoot up and eat into a lot of the increase we saw the prior year, and then we saw lower yields,” he said. “This year, to get the acres we needed, the price had to be attractive enough vs. other commodities.”

With tomato processors needing to replenish shrinking inventories, Montna said, canneries offered growers higher contract prices to encourage increased plantings. For 2023, CTGA announced a record price agreement with processors of $138 per ton for conventional tomatoes and $190 per ton for organic tomatoes. That is up from last year’s price of $105 per ton for conventional and $165 per ton for organic tomatoes.

“It really comes down to a supply-and-demand situation where you have to incentivize growers—the few that do it—because it’s a huge input-cost crop,” Yerxa said. “You spend upwards of $1,000 per acre just to get the transplants in and the bed prep before you even get any kind of a crop off.”

Fresno County farmer Don Cameron said his diverse farming operation makes “processing tomatoes a regular part of our program every year, organic and conventional.”

He said the record prices for processing tomatoes are welcome because “our costs just continue to rise, and I think growers need to be in the upper (price) range to be profitable growing this crop.”

“Our yields over the last five, 10 years have essentially flattened out,” Cameron added. “But this year is going to be an exception, at least in the southern part of the state where the yields have been very good.”

Costs to produce processing tomatoes increased substantially in the past six years, according to a July study by researchers at the University of California and UC Cooperative Extension farm advisors. A 2023 cost analysis for growing processing tomatoes in the Sacramento Valley and northern delta found that farmers face surging production costs, including for water, labor, fuel and fertilizer.

Rising expenses translate to costs of close to $6,000 per acre to plant, grow and harvest processing tomatoes, the study found. That is a 76% increase from 2017.

In discussing demand for processing tomato products, which are used in staples such as sauces, ketchup and salsa, Montna said the sector experienced an increase in demand during the COVID-19 pandemic. “We are now seeing a post-COVID world still adjusting to what the new normal is going to be,” he said.

“With inflation, you’re seeing people make different choices in the store,” he added. “But there’s a reliability and a sense of comfort that when you buy our product, you can have something that tastes good, and you feel comfortable feeding your family.”

— Christine Souza, assistant editor of Ag Alert, California Farm Bureau.

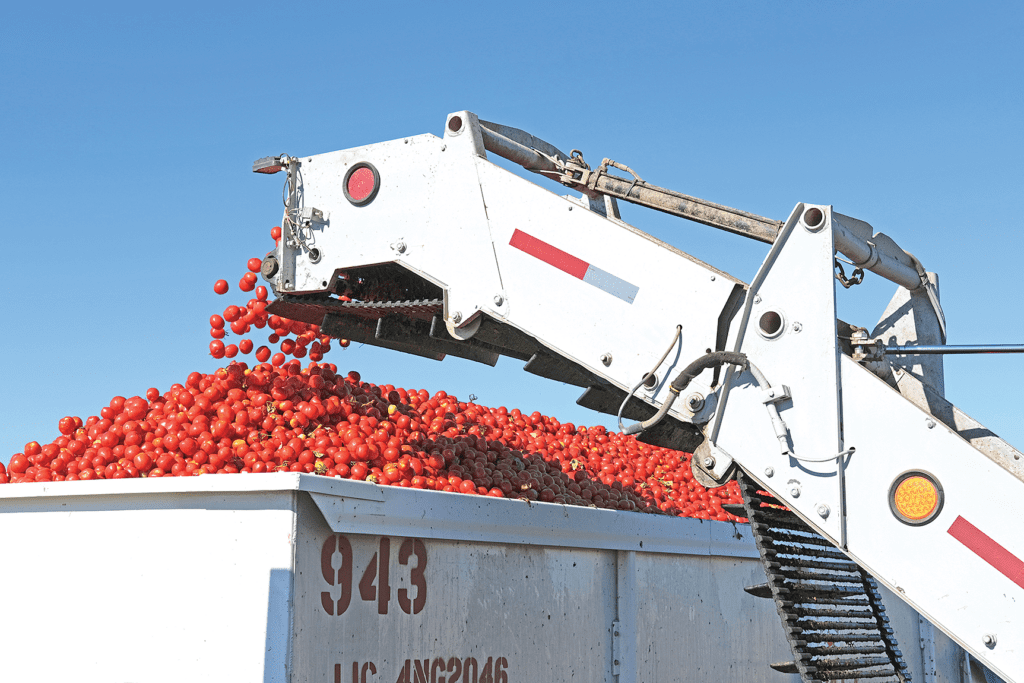

Top photo: California Sun Grower Services employee Eden Peña cleans debris from a tomato harvester in a Sutter County field. Growers say they fear delays in early-season planting could result in excess tomatoes needing processing all at once.