Apr 1, 2021Research station building reflects North Carolina investment in sweet potatoes

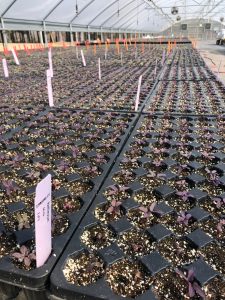

At first glance, the new building at the Horticultural Crops Research Station may not seem that remarkable. It’s a light beige metal building. 60 feet wide. 100 feet long. It’s distinguished by its reddish-maroon trim. Otherwise, it’s a near twin to the older building just beside it.

What it lacks in pizazz, the new building makes up for in its function and its value to the sweet potato research done on the station outside Clinton. It has more than doubled the station’s sweet potato storage capacity, according to station superintendent Hunter Barrier. The space also allows for more elbow room for researchers, their teams and the station employees.

“There’s a lot of sorting and going through sweet potato samples and seeing what project leaders want to plant,” Barrier said. “So we need room to get in there and sort everything out. We have more room to work now.”

In addition to the open workspace, there are also separate storage rooms in the new building. One holds large wooden bins of sweet potatoes while the other holds racks of plastic tubs – called “lugs” – filled with sweet potatoes. Both rooms have temperature and humidity controls so they can be used to store sweet potatoes for different purposes in the research process.

With the new building, the Horticultural Crops Research Station now has three sweet potato storage buildings. The last one was built in the early 80’s, and for several years now it’s been home to a sophisticated optical sorting machine for sweet potatoes. It takes up a considerable amount of space, especially when it’s in use. That has limited the floor space for other research activity. Now the two older buildings can be used for more long term storage and flex space as needed.

N.C. State University researcher Kenneth Pecota also said another reason space has gotten tighter with the old buildings is that researchers have had more sweet potatoes on their hands in recent years. They’ve needed to grow more, handle more, store more and ship more sweet potatoes to commercial processors. Those processors have been interested in testing more varieties for sweet potato fries. An increase in the volume of sweet potatoes at the research station called for an increase in space.

A reflection of collaboration

The funding that went into the building reflects the collaboration that helps North Carolina lead the sweet potato industry in the U.S. – from research to production on farms. The North Carolina Department of Agriculture paid for most of the building, but research teams from N.C. State University’s Department of Horticultural Science also contributed.

“The General Assembly approved us [NCDA&CS] to spend $300,000, and that money came from the sell of timber grown on NCDA&CS research stations. That basically purchased the building shell and constructed the interior storage rooms,” Barrier said. “In order to make it useable for sweet potato research this year, we relied on funding from the N.C. State sweet potato project leaders who will use the new facility – Craig Yencho, Jonathan Schultheis and Katie Jennings. Together they spent more than $45,000 to purchase ventilation system components, a control and alarm system, a concrete pad to connect the new building to the existing building and guard rails to protect the walls. With our operating budget here at the station we also spent more than six thousand, and then the SweetPotato Commission has committed an additional nearly $40,000.”

Yencho is the professor who leads N.C. State’s Sweetpotato and Potato Breeding and Genetics Programs. His team contributed $30,000 to the building. Schultheis and his team, which focuses on commercial production, contributed $10,000. Jennings and her team, which focuses on weed management, contributed $4,500.

“We couldn’t have done this project and had sweet potatoes moved in without collaboration and contribution from the project leaders,” Barrier said.

The contribution from the N.C. SweetPotato Commission will pay for an emergency generator large enough to provide back-up power for both the new storage facility and the older storage facility. The generator will ensure climate-controlled protection for valuable sweet potato germplasm (plants, parts or seeds used to grow new plants). It will also make sure a power outage doesn’t ruin research trials that test postharvest storage of sweet potato varieties.

“Craig’s group is chipping in on that particular expenditure too, so that’s another example of a partnership within a partnership,” said Michelle Grainger, the commission’s executive director. “It’s a piece of equipment that really is going to help protect our future and the future of the industry.”

A major goal of the research is to find a replacement for the Covington sweet potato, a variety Yencho and Pecota developed that has been a gold standard for quality and production for many years. However, Covington sweet potatoes aren’t resistant to guava root knot nematodes, which are microscopic plant-parasitic roundworms. The nematodes have been found in North Carolina soils since 2013, and they can cause significant damage to sweet potatoes and other crops.

So across the sweet potato industry, there’s interest in developing new varieties to ensure there is a future for sweet potato growers. In North Carolina, that means there’s an especially strong partnership between NCDA and NCSU to help secure that future. That partnership dovetails research station employees with horticulture science researchers, and it extends to the N.C. SweetPotato Commission, sweet potato farmers and processors.

“I can rely on Hunter and his team to handle all the field plots – apply all the fertilizer, manage all the crop production chemicals and manage all this infrastructure – and I can come from on campus and bring our resources to the table, and we work together in partnership. I don’t know of a single other state that does it that way,” Yencho said. “We have great resources to do research, and they’re spread across all these different environments. I don’t think many other places have that.”

Yencho was referencing the fact that sweet potato research takes place at other research stations too, including those in Clayton, Whiteville, Kinston and the Sandhills. Any of the state’s 18 research stations are potential testing grounds if a research project needed to explore from the mountains to the coast.

Growers have also shown to be willing participants in keeping North Carolina’s sweet potato industry strong, Grainger said. She said because many growers believe in the importance of research and working together, they have repeatedly allocated some of their land for additional research space.

“They actually incorporate their own staff to help collect data and monitor things,” Grainger said. “That’s very powerful too. I think a lot of people have an idea that farmers are very closed off and they’re very private – and to some extent I think there’s some truth to that – but in my experience, they want you to understand, and they want to be a part of helping to progress their crop or crops and helping ensure that there is a future well beyond themselves. That adds to that whole collective ecosystem of partnerships.”

Pecota and Yencho have certainly noticed the collaboration in North Carolina make a positive difference. A few decades ago, the outlook for sweet potatoes in the state was grim.

“One of the first SweetPotato Commission meetings Craig and I went to was back when things were not looking so good. Acreage was still going down and acreage was shifting over to Louisiana, and we were talking to growers, and they were basically saying ‘We’re telling our kids not to go into farming – not to go into sweet potatoes,’ and those kids are the people we’re working with now!” Pecota said.

The exciting part for Pecota and Yencho is that they’ve seen the collaborative efforts work. It’s resulted in great progress for the sweet potato industry in North Carolina. The need for a new sweet potato building is just one big physical sign of that progress.

– Brandon Herring, N.C. Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services

Photo at top: The new sweet potato storage building.