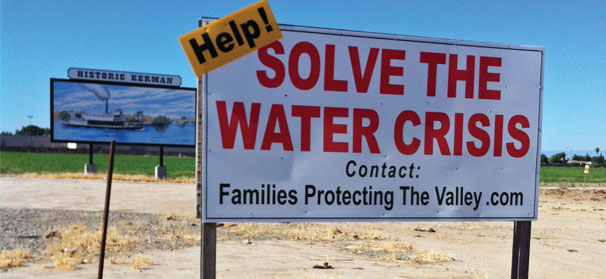

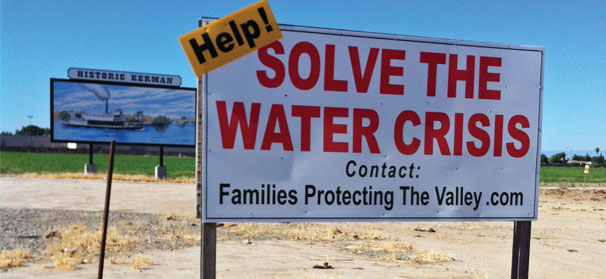

Mar 19, 2015California drought showing no signs of relenting

Although early February storms brought much-needed precipitation to California, they only made a small dent in the four-year-old drought, water managers said.

Many of the state’s vegetable growers said they still don’t expect any surface water deliveries and plan to reduce acreage and only plant fields with adequate groundwater supplies.

Growers of permanent crops, such as grapes and stone fruit, also have taken inventory and have removed marginal orchards or vineyards to focus what water they have on top-producing ground.

Water suppliers warn of cuts

Much of the agricultural land in central California is served by two large water systems: the State Water Project and the federal Central Valley Project (CVP). The California Department of Water Resources, which operates the state project, warned its 9,000 water rights holders on Jan. 23 of possible curtailments if dry conditions persist.

The Bureau of Reclamation, which operates the CVP, plans to make its initial allocation announcement in late February, said Louis Moore, deputy public affairs officer in Sacramento.

At the beginning of the current water year, Oct. 1, 2014, the CVP’s six main reservoirs had carryover storage of 3.1 million acre-feet – or 49 percent of the 15-year average, he said. That compares with carryover storage of 5.1 million acre-feet at the end of the 2013-14 water year.

An acre-foot, about 325,900 gallons, can meet the annual water needs of a family of four or five, according to the Department of Water Resources.

In February 2014, the bureau announced initial allocations of zero percent for most users, except for Sacramento River settlement and San Joaquin River settlement contractors, which received 40 percent of contracted amounts.

What the initial allocations will be this year will depend partly on February precipitation, Moore said.

But the water picture is not looking pretty. A Jan. 29 Sierra Nevada snow survey on Echo Summit just west of Lake Tahoe found snow water content of 2.3 inches, or just 12 percent of long-term average, he said. Spring snow melt makes up about 60 percent of reservoir storage.

“January is typically the wettest month of the year, and we’ve seen three of the driest Januarys, and we’re into the fourth driest in quite some time,” Moore said. “We have a smaller water supply than last year, which is a very difficult position to be in. There’s just no snow in the mountains to melt in the coming months, and the forecast right now is for dry long term.”

Early February storms brought up to a few inches of predominately rain in most areas, but long-term forecasts call for a high-pressure zone and dry conditions. Because the storms were warm, the snow level was high in the Sierras, adding little to the snowpack.

“Water is a good thing, so we’re happy to have the rain that we got,” Moore said. “The difficulty is the long-term effect of the drought. If we had several more of these systems in the short term, that would be fantastic.”

Although the Fresno-based Westlands Water District has yet to make allocation announcements, it began warning growers in October 2014 what to expect, said Gayle Holman, public affairs officer. The district is a CVP contractor.

As of early February, Holman said, “The bureau has the final say, but we’ve been preparing our growers since October to expect an initial allocation of zero.”

If that occurs, she said the district will likely see about 200,000 of its 575,000 total agricultural acres remain fallow.

In 2014, the district’s crop reports showed growers fallowed 206,000 acres and didn’t harvest another 13,000 planted acres because they ran out of water.

That compares to the 2013 season, where district growers fallowed 121,251 acres and left another 10,597 unharvested.

Once again, Westlands plans to buy water, should it be available and should growers be willing to pay for it, she said.

This year, Holman said she expected the price to be eight to 10 times what growers typically would pay for contract water.

Planning for the worst

Drought years also have different weather patterns that affect irrigation, said David Doll, a University of California Cooperative Extension farm adviser in Merced County.

“In drought years, spring tends to be a lot warmer than normal,” he said. “Water use in April and May is much higher” than the 30-year average of California Irrigation Management Information System data.

Growers, especially those with wells, typically will have to contend with increased salinity of irrigation water and manage accordingly, Doll said. That includes avoiding use of fertilizers high in chlorides.

Joe Del Bosque, who farms fruits and vegetables about 25 miles south of Los Banos, has ground within four water districts – all of them CVP contractors.

Del Bosque received no surface deliveries last year, and said he is prepared for that again this season. Adding to the challenge is he has no wells.

As a result, Del Bosque said he planned to remove 75 acres of asparagus after the spring harvest, leaving him with 125 acres. This comes on top of the 80 acres of asparagus he removed after the 2014 harvest.

His focus will be finding enough water to irrigate his melon fields and to keep his cherry and almond trees alive.

Del Bosque said he hopes to buy water again this season, but the price continues to climb.

“If you can find water, it’s extremely expensive right now,” he said.

Not long ago, Del Bosque said he spent $600-$800 for enough water to irrigate 1 acre. Last year, he spent $3,000-$4,000 for that same water.

Water costs also factored into growers removing about 25,000 acres of San Joaquin Valley grapes after the 2014 harvest, said Jeff Bitters, vice president of operations for the Fresno-based Allied Grape Growers. Of those vineyards, about 60 percent were winegrapes.

But Bitters said it would be incorrect to blame the drought entirely.

“Really, the reason for the removal is the market,” he said. “It’s just become uneconomical to farm certain grapes. Part of that cost is water and the availability of it.”

Paul Sanguinetti, a producer of diversified crops including processing tomatoes and walnuts east of Stockton, is in a slightly better water situation.

Stockton East Water District, which serves his operations, has surface rights in New Melones and New Hogen reservoirs and long-standing riparian river rights on Mormon Slough.

Sanguinetti, who also serves as district president, said the board hasn’t figured out whether or when water deliveries might occur.

Having weathered earlier droughts, Sanguinetti said he’s prepared for no deliveries.

In fields without irrigation, he planted a winter forage crop that he can chop for silage if it doesn’t rain. If it rains later this spring, Sanguinetti said he’d consider planting silage corn as a second crop.

Processing tomatoes will be planted to ground with wells.

Sanguinetti also plans to have a well drilled to irrigate his walnut orchards.

“I’ve always relied on surface water for them,” he said. “Even in years without surface water, we’re on a creek and it always had a large amount of drainage water, but I’m not taking any chances.”

– Vicky Boyd, VGN Correspondent