Jul 11, 2025MSU study shows farm labor changes, challenges

For the first time, the Mexican immigrant population in the U.S. has started to decline, creating new labor supply pressures for industries that rely on immigrant employees.

In a Michigan State University (MSU) study, researchers provide an overview of the farm labor market in Michigan, emphasizing changes in employment, wages and farmworker characteristics to highlight how the farm labor force has changed over the past 20 years.

While certain agricultural sectors have adopted new management practices and reduced their reliance on labor, others, including fruit and vegetable production and the dairy industry, still depend heavily on farm labor. This is primarily due to the unavailability of technology for specific farm tasks or the high costs associated with implementing robotic or mechanized equipment to replace human labor.

However, with the rising pressure on farm profitability due to high wages for farm labor, worker availability and low returns for raw agricultural products, the agriculture sector is faced with the challenge of finding labor solutions to keep farms in business.

The study indicates a 10% increase in Michigan farm wages would produce a 6.7% decline in farm employment and a 2.7% reduction in specialty crop production. The study finds that rising wages would cause regional incomes to rise by $78.2 million, primarily driven by increased labor income. However, the estimates suggest total regional output would drop by $51.1 million as agricultural producers reduce their production, reflecting a decrease in the value of economic transactions.

The study finds that while higher wages may boost overall labor income in the sector, they could also cause lower employment and reduce output.

Changing workforce

The farm workforce is evolving as Mexican immigration declines and traditional migrant populations age, the study found. The farm labor force in the U.S. consists mostly of immigrant workers from Mexico, and about half are not legally authorized to work in the U.S.

For many decades, the number of Mexican immigrants residing in the U.S. steadily increased, reaching more than 11 million in 2007. However, that workforce is beginning to decrease, which is placing new pressures on industries that rely on immigrant workers.

Evidence suggests the smaller volume of U.S.-based farm employees is causing growers to significantly change their production and labor management practices. Farm labor contractors bring workers to farms and growers are utilizing the H-2A visa program to address labor shortages. Factors that have contributed to the declining farm labor supply include increased educational attainment among rural Mexicans, demand for immigrant workers from competing sectors within the U.S. and a decline in migratory behavior among U.S. farm workers.

Industry sources argue that the H-2A program’s minimum wages, known as Adverse Effect Wage Rates (AEWR), exceed local wages, creating a disconnect from local farm labor conditions. They warn that higher labor costs could drive domestic farm businesses reliant on the H-2A visa program out of business, as they can’t pass on these costs to consumers.

Competition from countries with lower labor costs also adds pressure to the situation by putting downward pressure on farmgate prices. Despite growth in the H-2A program in Michigan’s Lake Region, its expansion has slowed, suggesting rising labor costs may be reaching a tipping point. Recently, legislation has been proposed to address some of these labor challenges but has failed to garner sufficient bipartisan support.

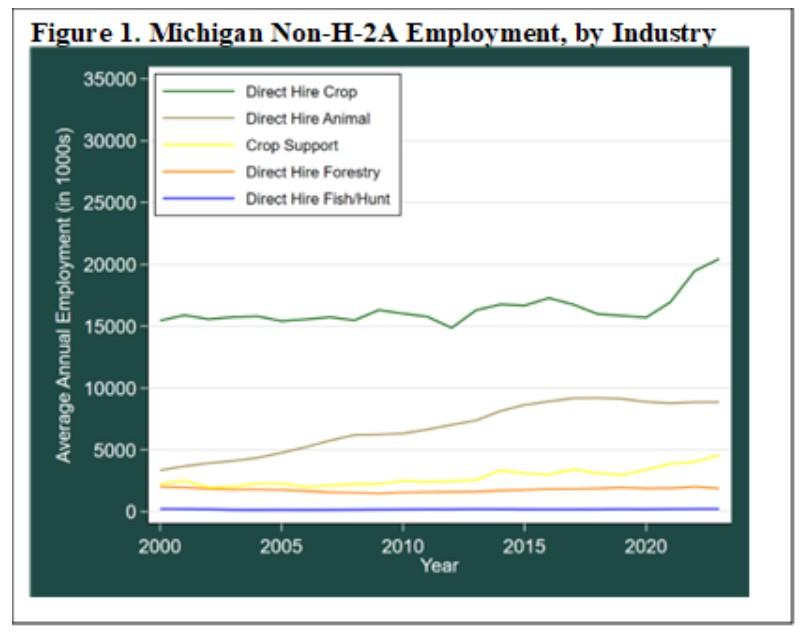

Non-H-2A employment

Non-H-2A agricultural employment in Michigan has been rising since 2000, but this trend could reverse moving forward. In 2023, there were more than 34,000 non-H-2A jobs on the books of Michigan agricultural employers in an average month.

Agricultural work is seasonal and fluctuates throughout the year. The peak employment months are during the summer, when the number of non-H-2A jobs on the books of employers exceeds 41,000. January is the month with the lowest employment, with just under 30,000 non-H-2A jobs.

Most of Michigan’s non-H-2A farmworkers are directly hired by crop farmers, with a smaller share in animal agriculture (Figure 1). A rising share of farmworkers, brought to farms by crop support workers, perform tasks such as tilling the soil, pruning, weeding and harvesting through contracts with farmers. The average annual employment of non-H-2A crop workers is approximately 20,000, with around 10,000 involved in animal production and another 5,000 in crop support services.

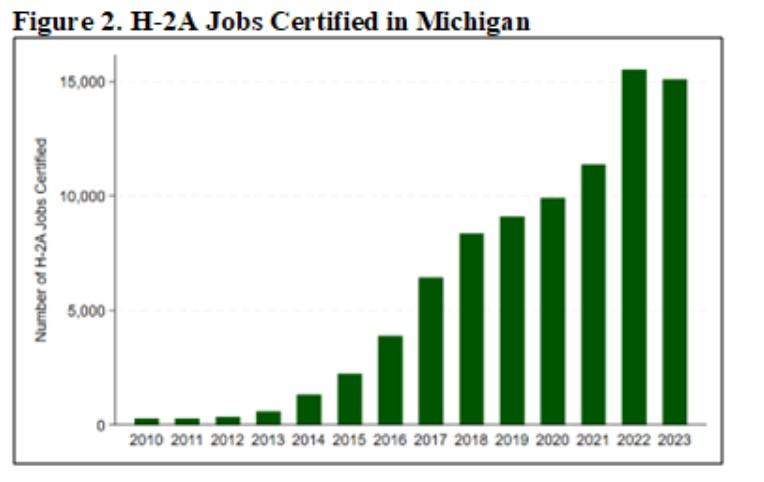

H-2A employment

H-2A employers must also follow other rules, including providing housing and paying for H-2A workers’ transportation to and from their home country. Employers must pay the highest of the state or federal minimum wage, the prevailing wage rate as determined by a State Workforce Agency, the agreed upon collective bargaining wage rate, or a super minimum wage known as the Adverse Effect Wage Rate (AEWR).

The binding wage rate for H-2A workers in Michigan is almost always the AEWR, so the AEWR sets the minimum wage for most H-2A employees. In recent years, H-2A employment has been rising throughout the nation and in Michigan. In fiscal year 2023, there were more than 15,000 H-2A jobs certified to work in Michigan (Figure 2). Most of these workers are employed in the western part of the state in Kent, Oceana, Ottawa, Van Buren and Berrien counties.

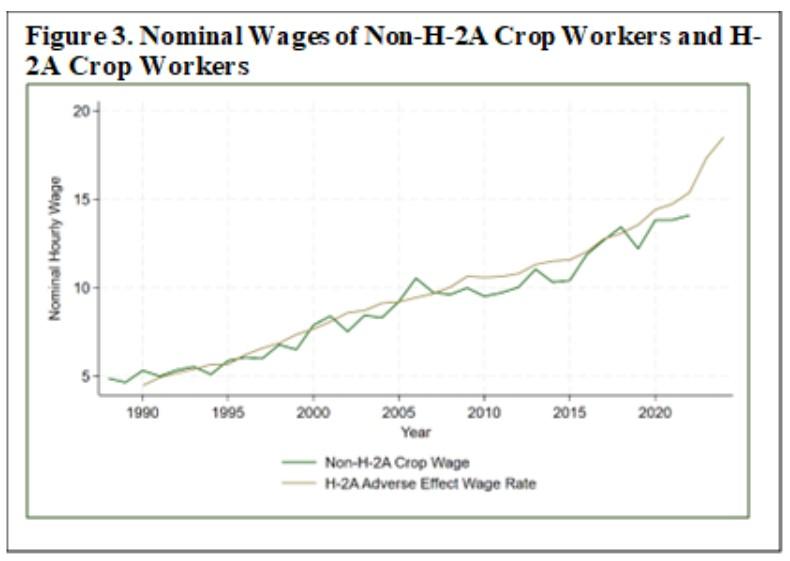

Declining labor supply raises farm wages

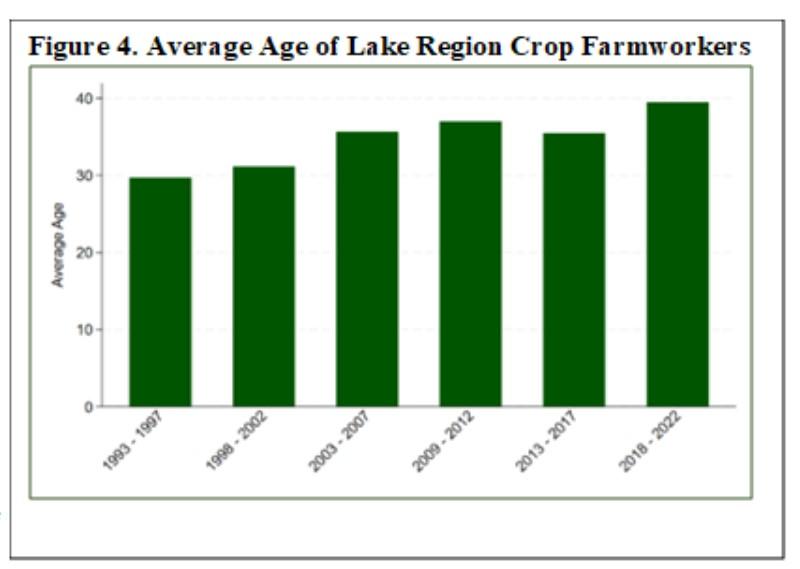

With the Mexican immigrant population declining, the domestic farm labor supply is aging and is not being replaced by young immigrant workers the way it once was. The average farmworker in the 1990s was much younger, as new immigrant workers replaced those who were aging out of the workforce. However, over the past three decades, the average age of Lake Region crop farmworkers has increased from 30 years from 1993-1997 to 39 years from 2018-2022. These statistics reveal that the domestic crop farm workforce is aging as workers who entered the country in the 1990s and early 2000s in their 20s and 30s are now in their 40s and 50s.

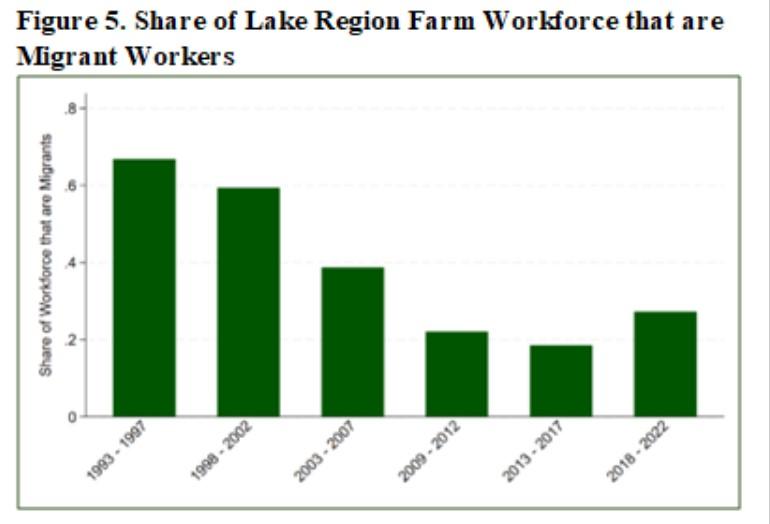

Additionally, the share of Lake Region farmworkers who are migrants traveling at least 75 miles to their place of work has declined rapidly over the past three decades. Figure 3 shows that between 1993 and 1997, 67% of the workforce was migrants, and that number decreased to 27% between 2018 and 2022.

The share of the workforce that migrates to do farm work in the Lake Region has declined significantly (Figure 4), reducing the geographic reach of local labor markets to attract workers who follow the crop during harvest time. These trends have created a situation where the domestic farm labor supply is declining, causing farm wages to rise.

Despite this trend, farm employment in Michigan has increased over the past couple of decades, suggesting that the demand for farm labor is outpacing the decline in the supply, causing wages to rise and attracting some new farm employees. As the domestic farm labor force declines, the use of the H-2A visa program to fill labor shortages has become more common.

By Zachariah Rutledge, Philip Kaatz, Emily Lavely and Ben Werling

Rutledge is an MSU assistant professor and Extension economist; Kaatz is a field crops educator in the Lapeer County Extension office; Lavely is a tree fruit educator for Michigan’s West Central region and Werling is an MSU Extension vegetable educator.